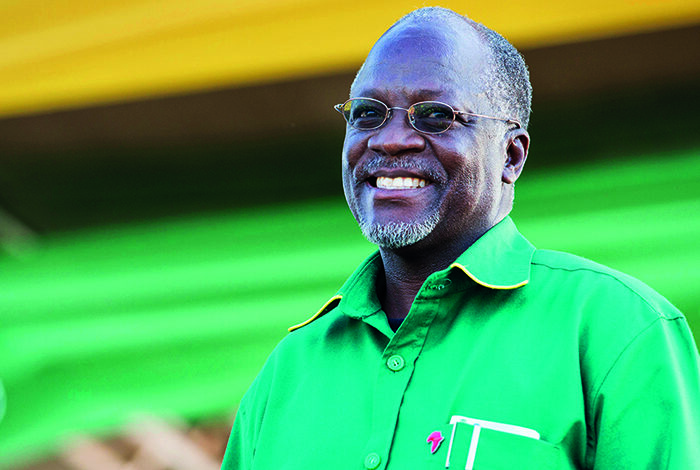

Before he was hospitalized, the president urged Tanzanians to pray for three days to defeat the new coronavirus variants. COURTESY PHOTO.

Around East Africa, multitides are sharing tributes to Tanzania’s president John Pombe Magufuli who passed away at age 61.

He died on Wednesday from “heart complications” at a hospital in Dar es Salaam, Mrs. Samia Suluhu Hassan, the Vice-President of Tanzania said in an address on state television. She announced 14 days of national mourning and said that flags would fly at half-staff nationwide.

A devout Roman Catholic, John Pombe Magufuli made international headlines over among others his atypical approach to tackling the pandemic during his stay in office.

Nicknamed “The Bulldozer” for his authoritarian leadership, Magufuli described the virus as a demon and declared a spiritual war against the disease, saying, “COVID-19 cannot survive in the Body of Jesus (and) will be burned away.”

Instead of masks, lockdowns and social distancing, the East African leader encouraged his country to rely on the power of prayer, holy communion, traditional healing techniques like steam inhalation, and natural “cures” such as ginger and lemonade.

In his tribute, Ugandan Pastor David Omongole of Christos Rhema Church, said Mugufuli, “you ran your race with a rare and admirable boldness.”

Magufuli refused to shut down churches, mosques and other places where people gather for prayers. At the time, he said churches and mosques had to remain open as that is where “real healing” takes place.

The government never updated its official number of coronavirus infections—509—since April 2020. For this, he was criticized for mixing “faith and science.”

For example, journalist Khalifa once tweeted: “Tanzanians elected a president, not a pastor or a sorcerer.” That aside, a handful of religious leaders also ridiculed Magufuli for what they called “substituting science with religious beliefs.”

Historians asserted the arguments advanced by Mr. Magufuli that faith should be mobilized to defeat the virus shows the endurance of ideas that can be traced back to medieval Europe. Some religious authorities then suggested citizens gather to pray and fight the Black Death, a plague that ultimately killed more than 50% of some communities across Europe in the 14th century.

“We are not an island,” the secretariat of the Tanzania Episcopal Conference said in a widely shared statement.

The clergy urged followers, which include the president, to pray but also to adopt measures long practiced in the rest of the world, including avoiding public gatherings and close personal contact. The church’s newspaper on January 29 stressed in a large front-page headline: “There is corona.”

Magufuli responded May 3: “Let us continue praying to our God. God exist! There are even religious leaders who have forgotten God whom they have been preaching to us every day … and this is the time to test the faith of the leaders we have, even the religious leaders.”

While other African countries seek millions of doses, Magufuli according to Christianity Today, accused people who had been vaccinated overseas of bringing the virus back into Tanzania. He also questioned whether the vaccines work.

Another Ugandan Pastor, Umar Mulinde of Gospel Life Church International, described Mugufuli as a “real Pan Africanist.”

“Your name has been registered in the good books of the true son’s of Africa. You will be remembered forever,” he said.

After taking office in 2015, Magufuli immediately began to impose measures to curb government spending, such as barring unnecessary foreign travel by government officials, using cheaper vehicles and board rooms for transport and meetings respectively, shrinking the delegation for a tour of the Commonwealth from 50 people to 4, dropping its sponsorship of a World AIDS Day exhibition in favour of purchasing AIDS medication, and discouraging lavish events and parties by public institutions (such as cutting the budget of a state dinner inaugurating the new parliament session). Magufuli reduced his own salary from US$15,000 to US$4,000 per month.

Magufuli suspended the country’s Independence Day festivities for 2015, in favor of a national cleanup campaign to help reduce the spread of cholera.

Magufuli personally participated in the cleanup efforts, having stated that it was “so shameful that we are spending huge amounts of money to celebrate 54 years of independence when our people are dying of cholera”. The cost savings were to be invested towards improving hospitals and sanitation in the country.

Magufuli was married to Janeth Magufuli, a primary school teacher, and had three children together.

First elected as a Member of Parliament in 1995, he served in the Cabinet of Tanzania as Deputy Minister of Works from 1995 to 2000, Minister of Works from 2000 to 2005, Minister of Lands and Human Settlement from 2006 to 2008, Minister of Livestock and Fisheries from 2008 to 2010, and as Minister of Works for a second time from 2010 to 2015.

Running as the candidate of Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), the country’s dominant party, Magufuli won the October 2015 presidential election and was sworn in on 5 November 2015; he was re-elected in 2020.

He ran on a platform of reducing government corruption and spending while also investing in Tanzania’s industries, but was accused of having had increasingly autocratic tendencies seen in restrictions on freedom of speech and a crackdown on members of the political opposition.

Magufuli earned his bachelor of science in education degree majoring in chemistry and mathematics as teaching subjects from the University of Dar es Salaam in 1988. He also earned his masters and doctorate degrees in chemistry from the University of Dar es Salaam, in 1994 and 2009, respectively. In late 2019, he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Dodoma for improving the economy of the country.